So often, beautiful picture books form our introduction to the world of books and reading. Our guest blogger Lucy Mangan shares her journey of rediscovering the wonderful world of picture books as a parent.

I am, in all honesty (and who could lie on the Penguin blog? Only a pure sociopath), the last person in the world who should be talking to you about picture books. By age, upbringing, education and temperament I am still essentially trapped in the old-skool mindset that says words are the only thing that matters. Pictures are for decoration, and picture books the things you just have to get through before you can start on ‘proper’ reading.

And that, because I am nine parts twonk to one part reasonable human being, was the position to which I firmly cleaved until I started reading to my own child, who is now four years old. Now I know – picture books are where it’s at. Where it’s all at.

Look at Each Peach Pear Plum. Text: “Each Peach Pear Plum / I spy Tom Thumb”. The first line is basically madness. But it’s hypnotic, enchanting, seductive and – as the book goes on – immensely cheering, a sort of prototype inside joke. “I spy Tom Thumb” introduces the famous fairy tale character and directs us to the picture on the opposite page, where he’s hiding in a peach tree. From here – and I speak from experience – you can go in many directions. You can have a long discussion about peaches. Or trees. Or ladders, or “Why are plums?” You can explain who Tom Thumb is and quietly boggle internally at the fact that the Ahlbergs are metatextualising your toddler before you have even re-learned how to sneeze without weeing. Or, especially on your second, third or forty-fifth reading, turn the page to see who Tom Thumb will give way to – spoiler alert: he’s in the cupboard, and it’s…Mother Hubbard!

The point is – picture books allow your child to become fluent in two languages, minimum; the printed word and visual images and imagery. You forget that the latter requires just as much learning, interpreting and decoding as the former because you learn it so early that it simply becomes part of you, incorporated into what other, more romantic ages would call your soul. It’s not until your three year old looks baffled and asks “Why is that tree coming out of that man’s head?” that you realise that understanding perspective is a matter of nurture, not nature. “The tree isn’t, darling – it’s just behind him, further away.”

The point is – picture books allow your child to become fluent in two languages, minimum; the printed word and visual images and imagery. You forget that the latter requires just as much learning, interpreting and decoding as the former because you learn it so early that it simply becomes part of you, incorporated into what other, more romantic ages would call your soul. It’s not until your three year old looks baffled and asks “Why is that tree coming out of that man’s head?” that you realise that understanding perspective is a matter of nurture, not nature. “The tree isn’t, darling – it’s just behind him, further away.”

Now, when we read the few picture books I do remember from childhood – Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen, Come Away From the Water, Shirley, The Enormous Crocodile, the blood-soaked, colour-saturated pages of Struwwelpeter, which remains as entirely terrifying to me as it was when I was small and I don’t know WHY I’m putting myself through it again – I can begin to appreciate a tiny fraction of the art and the talent on show. The gradual widening of the frames in Where the Wild Things Are as Max enters the unlimited world of his imagination, until we reach the worldless double-paged spread in the middle – wall-to-wall wild rumpus. The two brilliantly contradictory stories being told in Shirley by her parents’ words and Shirley’s inner pictures. The jagged, evocative horrors accompanying Shockheaded Peter and his companion’s travails. The eye can no more drag itself away than the ear can refuse to hear the burrowing insistent rhymes (“’Me-ow!’ they said, ‘me-ow, me-o,/ You’ll burn to death, if you do so’”). Brrr.

Now, when we read the few picture books I do remember from childhood – Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are and In the Night Kitchen, Come Away From the Water, Shirley, The Enormous Crocodile, the blood-soaked, colour-saturated pages of Struwwelpeter, which remains as entirely terrifying to me as it was when I was small and I don’t know WHY I’m putting myself through it again – I can begin to appreciate a tiny fraction of the art and the talent on show. The gradual widening of the frames in Where the Wild Things Are as Max enters the unlimited world of his imagination, until we reach the worldless double-paged spread in the middle – wall-to-wall wild rumpus. The two brilliantly contradictory stories being told in Shirley by her parents’ words and Shirley’s inner pictures. The jagged, evocative horrors accompanying Shockheaded Peter and his companion’s travails. The eye can no more drag itself away than the ear can refuse to hear the burrowing insistent rhymes (“’Me-ow!’ they said, ‘me-ow, me-o,/ You’ll burn to death, if you do so’”). Brrr.

Nowadays there is such an embarrassment of riches in the land of the picture book that it is hard to believe that the genre itself (as we would recognise it, at least – books for children that included some illustrations have been around for at least four centuries) has only been with us for about 130 years, since happy historical circumstances combined in the latter half of the nineteenth century to give children’s literature artists Walter Crane, Randolf Caldecott and Kate Greenaway, printer-publisher Edmund Evans and sufficient technology and consumer appetite to bring all their gifts to fruition.

Nowadays there is such an embarrassment of riches in the land of the picture book that it is hard to believe that the genre itself (as we would recognise it, at least – books for children that included some illustrations have been around for at least four centuries) has only been with us for about 130 years, since happy historical circumstances combined in the latter half of the nineteenth century to give children’s literature artists Walter Crane, Randolf Caldecott and Kate Greenaway, printer-publisher Edmund Evans and sufficient technology and consumer appetite to bring all their gifts to fruition.

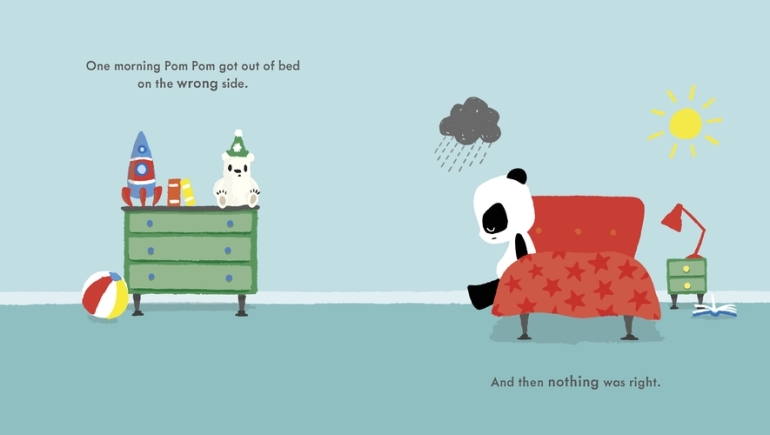

When I try and pick out a new picture book for my son, I am always overwhelmed by the dazzle of it all – the glorious colours, the endless invention, the energy, excitement and talent on display. We’re currently reading a couple of Puffin’s latest releases – Max the Brave (a kitten working up to his mouse-chasing destiny) written and illustrated by Ed Vere (written AND illustrated by! As my grandmother used to say – fun’s fun, but that’s sheer nonsense) and Sophy Henn’s Pom Pom Gets the Grumps (Pom Pom is a panda, and having a bad day). “What’s he doing?” said Mangan minor, pointing at Max. Well, Ed Vere put some black marks on a page that look like a courageous kitten then added a green triangle at his neck in such a way that it looks like it’s moving. “He’s flourishing his cape,” I said. It’s a miracle, isn’t it? With a bit of luck he won’t notice. It will just become part of his soul.

When I try and pick out a new picture book for my son, I am always overwhelmed by the dazzle of it all – the glorious colours, the endless invention, the energy, excitement and talent on display. We’re currently reading a couple of Puffin’s latest releases – Max the Brave (a kitten working up to his mouse-chasing destiny) written and illustrated by Ed Vere (written AND illustrated by! As my grandmother used to say – fun’s fun, but that’s sheer nonsense) and Sophy Henn’s Pom Pom Gets the Grumps (Pom Pom is a panda, and having a bad day). “What’s he doing?” said Mangan minor, pointing at Max. Well, Ed Vere put some black marks on a page that look like a courageous kitten then added a green triangle at his neck in such a way that it looks like it’s moving. “He’s flourishing his cape,” I said. It’s a miracle, isn’t it? With a bit of luck he won’t notice. It will just become part of his soul.

Puffin’s Max the Brave by Ed Vere and Pom Pom Gets the Grumps by Sophy Henn are both out now.

Follow Lucy on Twitter @LucyMangan.

Follow Lucy on Twitter @LucyMangan.

Photo: Stylist Magazine.

Picture books are where it’s at. Where it’s all at.

So often, beautiful picture books form our introduction to the world of books and reading. Our guest blogger Lucy Mangan shares her journey of rediscovering the wonderful world of picture books as a parent.

I am, in all honesty (and who could lie on the Penguin blog? Only a pure sociopath), the last person in the world who should be talking to you about picture books. By age, upbringing, education and temperament I am still essentially trapped in the old-skool mindset that says words are the only thing that matters. Pictures are for decoration, and picture books the things you just have to get through before you can start on ‘proper’ reading.

And that, because I am nine parts twonk to one part reasonable human being, was the position to which I firmly cleaved until I started reading to my own child, who is now four years old. Now I know – picture books are where it’s at. Where it’s all at.

Look at Each Peach Pear Plum. Text: “Each Peach Pear Plum / I spy Tom Thumb”. The first line is basically madness. But it’s hypnotic, enchanting, seductive and – as the book goes on – immensely cheering, a sort of prototype inside joke. “I spy Tom Thumb” introduces the famous fairy tale character and directs us to the picture on the opposite page, where he’s hiding in a peach tree. From here – and I speak from experience – you can go in many directions. You can have a long discussion about peaches. Or trees. Or ladders, or “Why are plums?” You can explain who Tom Thumb is and quietly boggle internally at the fact that the Ahlbergs are metatextualising your toddler before you have even re-learned how to sneeze without weeing. Or, especially on your second, third or forty-fifth reading, turn the page to see who Tom Thumb will give way to – spoiler alert: he’s in the cupboard, and it’s…Mother Hubbard!

Puffin’s Max the Brave by Ed Vere and Pom Pom Gets the Grumps by Sophy Henn are both out now.

Photo: Stylist Magazine.

Share this:

Related